Cold Warriors is a formidable, engrossing and almost flawless achievement. Its central argument takes the following form. Because of the existence of nuclear weapons and the consequent super-power military stalemate, the long Cold War struggle between the Soviet Union and the United States was, to a quite unusual extent, fought on the field of culture. The two contending visions of the future — Marxist-Leninist Communism or liberal-democratic Capitalism — were reliant on what writers produce, symbolism and ideology.

Duncan White’s subtitle, Writers Who Waged the Literary Cold War, is misleading. His study is of those writers whose work was shaped by the long Cold War or who even influenced its outcome. Several of White’s subjects were indeed warriors. Some were acute observers. Others became entangled in the Cold War web against their will.

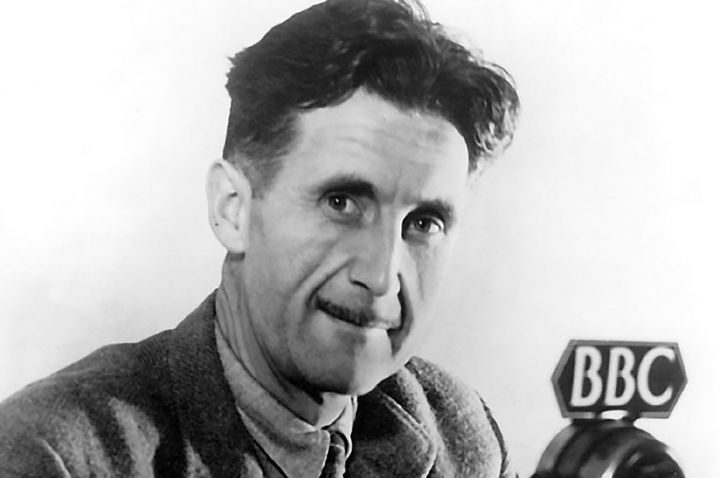

Two of White’s principal subjects — Arthur Koestler, the author of Darkness at Noon, and George Orwell, the author of Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four — did engage in literary warfare, hoping to convince their contemporaries, especially those on the left, that the equation of Soviet Communism with democratic socialism or, even more grotesquely, with humanitarian values, was a category error of the most dangerous kind. “The sin of nearly all left-wingers from 1933 onwards”, Orwell wrote, “is that they wanted to be anti-Fascist without being anti-totalitarian.”

Possibly the wisest sentence about the historical imagination was coined by the historian of feudal law, FS Maitland. In slightly condensed form: “What is now in the past was once in the future.” At the beginning of the Cold War both Orwell and Koestler genuinely feared that the future might belong to totalitarianism. White does recognise this, but only partially. In 1946 Orwell sent a British intelligence agency the names of 35 pro-Soviet fellow travelling intellectuals who might be Soviet agents. One, Peter Smollett, actually was. White raps Orwell on the knuckles. “For the author of Nineteen Eighty-Four, this was a surprising act of complicity.” If the stakes were as high as the destiny of humankind, co-operation with the intelligence service of a liberal democracy does not seem to me problematic, or at least not self-evidently so.

A more significant issue of this kind concerns the Congress for Cultural Freedom, launched in Berlin in 1950. The Congress was secretly funded by the CIA and guided from Paris by a CIA agent. In 1965 the CIA’s funding of the Congress and the intelligent monthly magazine, Encounter, was exposed by outstanding investigative journalism. White is more critical of the CIA’s covert operation to win what insiders called “the mind of Picasso” than seems just. While the Congress was being outed, at least 500,000 Indonesian left-leaning villagers were being slaughtered by General Suharto’s Army with the assistance of the CIA. The silence of the Western anti-Communist camp here is to my mind a far more troubling matter than the CIA’s payment of Encounter’s printing bill of which one of its editors, Stephen Spender, was genuinely ignorant.

Other White subjects on the Western side of what was once called “the iron curtain” - Graham Greene and John Le Carr - were not Cold Warriors but incomparable Cold War observers. Greene’s instinct led him to Vietnam before the Americans arrived and to Cuba before Castro. Somehow, through the power of uncanny political imagination, Greene foretold in The Quiet American the coming catastrophe of the Vietnam War, and in Our Man in Havana the fiasco of the CIA’s Bay of Pigs invasion and the near-apocalypse of the Cuban missile crisis. For his part, Le Carre, in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, robbed the world of espionage —with its shabby moral compromises and professional betrayals — of all James Bond-style romance.

While Orwell and Koestler were waging literary war, within the Soviet Union war was being waged upon two other principal subjects of White’s — the Russian civil war fictionalist Isaac Babel, and the mystical poet Anna Akhmatova. Although Babel paid his dues to Stalin in 1934, praising him for his “words… wrought of iron, how tense they are, how muscular”, this was of course of no avail. Babel was shot in his prison cell in 1940. On the eve of his murder, in an act of extraordinary courage, Babel withdrew his “confession”.

Akhmatova, the greatest Russian poet of her age, was defamed at the beginning of the Cold War as a decadent pessimist and expelled from the company of worthy Soviet “social realist” writers, a form once described as “boy meets girl meets tractor”. One of the most extraordinary passages in Cold Warriors is her description of the Stalin Terror. “Shakespeare’s dramas… are trifles, child’s play, in comparison with what we had to live through… Mute separations, mute black, bloody events in every family. Invisible mourning worn by mothers and wives. Now the arrested are returning and two Russias stare each other in the eyes.”

As White shows wonderfully well, writers played a significant part in the ultimate collapse of the Soviet Union. Courage steadily mounted as physical force declined. In 1957 Boris Pasternak allowed his great but anachronistic “nineteenth-century” novel, Dr Zhivago, to be published in the West. As a result he was defamed, strong-armed into returning his Nobel Prize, and driven into lonely “internal exile”. His death in 1960 was greeted by what White describes as “calculated silence”.

At this moment, Andrei Sinyavsky began publishing in the West under the pseudonym, “Abram Tertz”. Sinyavsky openly mocked his fellow writers and his prospective jailers. “Can there be a socialist, capitalist, Christian or Mohammedan realism?... [P]erhaps it is only the nightmare of a terrified intellectual.” His identity was eventually discovered. Sinyavsky and his co-defendant, Yulii Daniel, were the first Soviet writers to be tried in public. Sinyavsky was sentenced to seven years' hard labour.

In the Khrushchev literary “Thaw”, a former labour-camp inmate, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, was permitted to publish an account of the experience, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. To put it mildly, Solzhenitsyn was not done. He arranged for his novels, Cancer Ward and The First Circle, to be published abroad. And he composed the first history of the Soviet labour-camp system, based on the testimony of more than 200 inmates, zeks. The Gulag Archipelago was a vast, searingly sarcastic, revolutionary work. In arguing that the system of secret police and labour camps was not a Stalinist aberration but present at the Leninist foundation, The Gulag undermined the legitimacy of the Soviet state. Solzhenitsyn was not shot or now even imprisoned but, in 1974, forcibly expelled to West Germany. Thankfully but fatally, the Soviet leadership had lost its taste for blood.

Cold Warriors is based on wide-ranging scholarship that draws on the substantial library of books written in recent years (in English) on the major figures and incidents involved in the literary Cold War. It is also impeccably edited; in its 736 pages I noticed only one error. (Vladimir Bykovsky should be Bukovsky.) Its argument however is not without flaws.

Among the writers it studies not one is a political theorist. However for many Cold Warriors, totalitarian political theory was fundamental. The concept of totalitarianism provided the bridge connecting Soviet-style Communism with the evil of Nazi Germany. And it was the sharp distinction between totalitarian and authoritarian regimes that allowed Cold Warriors to focus on the crimes of Communism while turning a blind eye to the often greater crimes of their anti-Communist allies, “our bastards”, in Latin America and South-East Asia. A discussion of the early work of Hannah Arendt in her seminal The Origins of Totalitarianism, for example, would have provided White with a truer account of the worldview of many Cold Warriors.

In a discussion of the Berlin launch of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, White argues that Koestler’s “absent antagonist” was Jean-Paul Sartre. The political force represented by Sartre — anti-anti-Communism — is also largely absent from White’s account of the Western Cold War. In its early phase, the principal antagonists were Communists and anti-Communists; in the latter phase, anti-Communists and anti-anti-Communists. One side called the other “useful idiots” and “fellow travellers”. The other replied with charges of “McCarthyism” and “war-mongering”.

Finally, White’s account is limited by its Euro-centrism. What happened in China was a critical element in the Cold War arguments in the West. Nor did Communism collapse, as White implies, with the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Rather, in the form of Chinese “Market-Leninism”, it is shaking and shaping our world.

On June 4 1989, the Soviet Union tolerated a free election in Poland where non-Communists won all but one of the contested seats. On that very day, tanks rolled onto Tienanmen Square in Beijing crushing democratic hopes. Communism in Europe and Asia now parted company. The Cold War was over. The legacy of 1917 was not.

Originally published by The Sydney Morning Herald.