La Trobe Library is hosting an exhibition of popular and rare Australian titles from the personal collection of Stuart Kells, Adjunct Professor, La Trobe College of Arts, Social Sciences and Commerce. The exhibition encompasses the genres of Romance, Crime, Western and Science Fiction from key publishers including Phantom Books, Currawong Publishing and Transport Publishing. This Opinion piece is based on Professor Kells’s first reading associated with the exhibition.

***

This is the second event associated with the Golden Age of Pulp Fiction exhibition at La Trobe Library.

Last week, we launched the exhibition, which consists of a collection of Australian pulp fiction works from the middle decades of the twentieth century.

The works were produced in massive quantities and at an incredible pace.

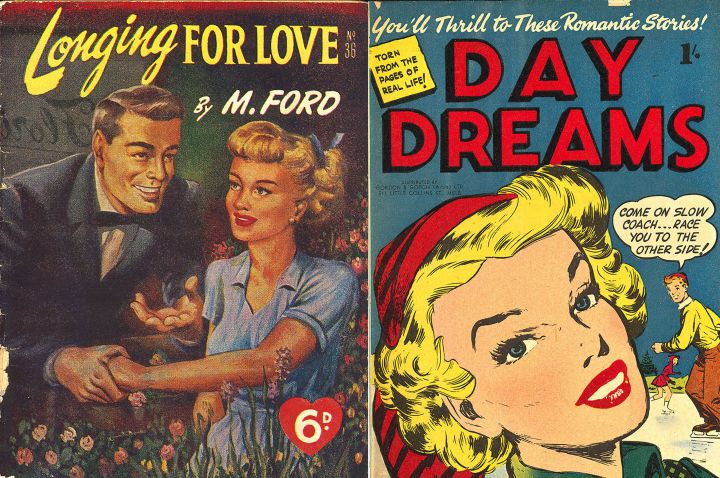

Noted for their vivid cover art and lurid titles, they satisfied an appetite for fast entertainment in the era before television.

Today, my focus is on one of the main pulp genres: romantic fiction.

This alone is an enormous field.

It includes books and magazines, some of them one offs, others produced by series publishers such as Harlequin and Mills and Boon.

Some romance works were printed in prose, others as comics and graphic novels.

Some were the work of local authors. Many were foreign reprints.

Romances were penned by male and female authors, often writing under allonyms and pseudonyms.

The genre branched into a multitude of sub-genres, such as Teen Romances, Gothic Romances and various Occupational Romances – such as nursing detective stories and flight attendant stories.

Adelaide Humphries’s work, Flight Nurse, combines flying and nursing.

'Young, dedicated…and in love…

‘I always wanted to meet a beautiful Southern Belle, especially a Georgia Peach – mind if I call you ‘Peaches’?’ asked tall, broad-shouldered Major Jerry McGuire.

Despite her youth and bright blue eyes, Valerie Lane minded terribly. It was a ridiculous name for a dedicated nurse engaged in the difficult work of rescuing Air Force pilots…and to Valerie – newly arrived at her post in the fascinating city of Tokyo – her work seemed all-important…

But to Major McGuire and to a young flier from her home town whose life she saves, Valerie was more than an ‘angel with wings’ – she was a warm, beautiful woman, a woman to be loved…’

Recurring themes and concepts in the romance genre include anxiety about marriage, anxiety about sex, anxiety about the choice of a partner, the fear of ‘buyer’s remorse’ in the choice of partner, and an overriding pressure to adhere to social rules.

These tropes permit all sorts of authorial play, such as where readers’ expectations are thwarted, and where social rules are broken in creative and subversive ways.

Part of the attraction of the romance genre is its complex relationship with convention and transgression.

There is a fine line between romantic and ‘adult’ literature, also known as smut.

By skirting up against the edge of respectability, the romance genre flirts with what is disreputable, and helps define both what is permissible and what is not.

In his History of Sexuality, Michel Foucault noticed something similar about eighteenth and nineteenth century sex manuals and moral treatises.

Romance writing has long been disparaged as a secondary or trivial form of writing.

Now, though, it is being reappraised and revalued.

As recently as this weekend, romance writing was a focus of the Melbourne Writers Festival.

There are several reasons for this reappraisal.

One is that genre fiction in general is now better understood and appreciated.

Another is that the boundaries between the genres are noticeably soft and fluid.

Romance spills over into adventure, for example, as well as into crime and even sci-fi, horror and ‘weird tales’.

The book ‘Longing for Love’ in this exhibition was published by the Invincible Press, an Australian imprint mainly known for crime stories and westerns.

The packaging and branding of the Invincible titles was consistent across the different pulp genres, as was the process and style of writing.

A deeper reason is that the romances deal with universal and enduring themes.

La Trobe medieval scholar Dr Stephanie Downes was at the pulp exhibition launch.

Stephanie’s work has included looking at similarities between depictions of faces in the middle ages, and depictions of faces today – including in emojis.

Following a similar train of thought, the way people are shown in these covers can be traced and matched to early modern and late medieval depictions of people.

And there are thematic connections, too, in the texts themselves.

Unequal lovers. Love triangles. The battle for the pants. Strange wives. Lewd grooms. She-devils.

All these topics were core themes of late medieval romances and early modern prints and broadsides.

They functioned as social propaganda, setting out desired modes of conduct, and the perils to avoid.

(Parallel genres in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries criticised the behaviour of peasants and priests.)

The ‘unequal lovers’ theme focuses on objectionable pairings: older man and younger woman; rich man and poor woman; and rich woman and poor man.

That theme was popular in sixteenth century Nuremberg, for example, and it was also popular in twentieth century pulps, appearing in romance titles such as Reckless Moment, Childhood Sweetheart, Shameful Love, Marriage of Convenience, A Legacy of Love, A Private Affair, The Leaping Flame, and A Heart in Doubt.

Maysie Grieg’s Reluctant Milionaire is a further example.

‘Cara,’ he whispered. ‘I love you – I love you…Come back with me to my apartment…’

‘Oh, please – please don’t ask.’ Her voice broke. ‘I love you, but I can’t go back with you.’

‘It doesn’t make sense,’ he said, the male in him very much on the rampage. ‘And even if you don’t love me, you might come back…for a little while. You say you’re grateful –’ His voice grew hoarse. ‘Am I to have no reward, Cara…?’

Professional Lover, the story of Starr Thayle and Rex Brandon, is another.

She felt his kiss on her lips , on her cheeks, on her throat…

‘Do you despise me very much ?’ he asked at last. And there was a note of humility in his voice which, to Starr Thayle, didn’t seem in keeping with his character at all.

‘Does it matter whether I despise you or not?’ she asked presently.

Rex Brandon nodded slowly. ‘I think it does.’

Rex Brandon, movie idol of millions, had fallen in love with her. Most women would give anything just to be seen in his company. Yet Starr Thayle was uncertain. Could a man who had been accorded so much female devotion ever become a faithful husband? Her final decision brings a crashing climax to this flaming tale.

‘Love triangle’ examples from the pulp romances include Three Loves, Heartbeat of Jealousy, For Better For Worse, Naked Passions, Dr Jeremy’s Wife, and Pilgrim Heart by Vivian Stuart. (‘Only when danger threatened did Francesca know which of the two men she loved!)

The novel Spotlight is another love triangle.

‘You’re in love with my husband!’

Rosalyn’s lips drew thin and then curved up in a smile that was pure malice.

‘You’ve always loved him, haven’t you?’ she asked her sister.

‘I hate you,’ Alix cried furiously.

‘Well I’ve divorced Mike,’ Rosalyn laughed. ‘Why don’t you try to get him? Try to be happy with a second-hand husband … What’s stopping you? Is it because you know that Mike still loves me? Is it because every time he looks at you, you wonder if he is seeing me instead?’

A gripping novel of two sisters who wanted the same man.

Clarkson Crane’s, Naomi Martin (also known as Frisco Gal) describes a variant situation: a love quadrangle.

‘A rich man’s darling.

A young man’s slave.

A strong man’s passion.

All three were hers for the choosing.’

Confessions: (occupation housewife) by ‘Dorothy Les Tina’ is another example of a love quadrangle.

Three men loved Darcie…but not one could help her.

Chuck knew she was restless and young. He gave her his heart…but she wanted her freedom.

Thad knew that she tortured herself, and he gave her his understanding…but Darcie was lonely.

Sid gave her something to believe in and he needed her badly…but she still didn’t know what she wanted.

No man could help Darcie till her own heart answered – which was the only man who could rouse her and give her true happiness?

Stories about different gender roles included Strange Wife, Phantom Emperor and Odd Girl Out.

These books foreshadow different concepts of gender and gender roles.

Some of them are legitimately seen as pioneering texts in LGBTIQ literature.

Phantom Emperor by Neil Swanson engages with gender roles in terms such as these:

She loved like a tigress…fought like a man.

Beautiful Maurine Dufresne wore the uniform of a captain , but beneath her disguise she hid the heart of a woman crying for love…

When huge, handsome Guerdon Warrener was placed under her command, she knew at once that she wanted him.

But could he see the woman beneath her cropped hair…discover her beauty hidden in tight breeches and a cross-belt?

A related sub-theme is ‘the battle for the pants’, which occurs in many films from the period, as well as stories such as Business and Pleasure, Whip Hand, and Career Wife.

Some of the books combine the different sub-themes, such as unequal lovers and love triangles.

Take for example Hidden Boundary by Frances Sarah Moore.

‘When Alfreda married wealthy Simon Overden for security, she knew in her heart that she still loved another man. Should Alfreda continue this masquerade, or should she leave the great mansion forever?’

As with crime novels and medieval romances, jealousy and adultery are recurring themes and a central interest in the pulp romances:

Elizabeth Seifert’s Home Town Doctor is an example.

The doctor and his wife had every reason to expect happiness in their own town. But a new doctor’s wife upset its delicate balance.

Dr and Mrs Adams … were a charming couple – a handsome, talented doctor and his lovely wife – and they reflected the small town’s best image of itself.

But when another doctor – and his alluring wife – moved into town, a crisis loomed that Lulu Adams had to meet with a single drastic step.

One Wild Oat by MacKinlay Kantor:

‘Maybe I shouldn’t really have come. I mean – well , I’ve never done anything like this before.’

His face broke into a grin, his brows were arched. ‘My dear girl,’ he said, ‘you can’t abide all your life by Middlefield standards! Not when you have so much to offer…’

Isabelle was thinking that she might take a brief holiday from marriage.

For better, for worse:

Sherry and Jimmy Maxwell began their married life at a lonely mountain retreat where everything was clean and beautiful, a perfect background for their pure, young love.

They thought their life would always be like this, that their honeymoon existence would overflow the rim of the curving mountains into the valley of the everyday world that awaited them.

But suddenly, the Maxwells were jolted from their private heaven as a cruel wave of jealousy washed the stars from their eyes and almost dashed their marriage against jagged rocks.

The continuity of themes over the past five centuries is striking.

And the origins of the stories can be traced back even earlier, to classical and Biblical times.

What are we to make of this?

One possible conclusion is that the stories capture and speak to our subconscious.

The different anxieties plausibly reflect something fundamental about urban life and the human condition.

An alternative conclusion is that the stories don’t speak to us at all: that they have very little to do with us as individuals, instead belonging to a meta-text that transcends time and obeys its own rules.

More than just the striking cover art, it is questions of that scale and difficulty that help explain the new interest in this old genre.