When Liberal Party MPs dumped Tony Abbott for Malcolm Turnbull in September 2015, they could hardly have pleaded ignorance of the turmoil they were creating for themselves. The fact they were in government could largely be credited to the Labor Party having torn itself apart in the Kevin Rudd-Julia Gillard leadership wars.

Almost three years later, veteran political journalist Paul Kelly believes Australian conservatism is in crisis:

Conservatism is consumed by confusion over its principles and purpose. It is fragmenting in party terms – witness the Coalition bleeding votes to Hanson’s One Nation and Cory Bernardi’s Australian Conservatives. With John Howard long gone, it is devoid of any authority figure in office able to hold the movement together and retain it within the party. Abbott remains its figurehead with the faithful but his internal standing has nosedived.

Much as Rudd did for Gillard’s entire prime ministership, Abbott continues to stalk Turnbull, using his media allies to insert himself in national debates whenever possible. This delights his supporters, but infuriates those Liberal colleagues more interested in governing than fighting internal battles

But can Abbott and the hardline conservative base succeed in reclaiming control of the Liberal Party?

The ‘delcon’ insurgency

In April 2016, conservative Daily Telegraph columnist Miranda Devine came up with the memorable term “delcon” to describe those “delusional conservatives” who remained firmly in the Abbott camp following the Turnbull coup. “The Delcon movement is tiny but viciously punitive to those it regards as heretics,” she wrote.

Devine had in mind prominent right-wing figures such as James Allan, a law professor at the University of Queensland, and John Stone, the former Treasury Secretary and National Party senator. Following the coup, both were quick to announce they would never vote for the Liberal Party “while led by Malcolm Turnbull and his fellow conspirators.

” But Devine’s delcon jibe did nothing to make them reconsider their positions. If anything, it hardened their resolve. Allan wore the term with pride, and re-affirmed his position that:

with Malcolm in charge it’s actually in Australia’s long-term interest to see the Coalition lose this next election, for the long-term good of party and country.

Stone preferred the term “dis-con” – claiming to be a disaffected, not delusional, conservative – and argued that voting against the Liberals was an act of principle intended to teach the party a lesson about loyalty.

Meanwhile, Stone and Allan have used every opportunity to urge the Liberal Party to restore Abbott to the leadership. They were especially emboldened by Turnbull’s disastrous election performance in 2016, which increased the power and influence of the Liberal Party’s right wing, even as it remained in the minority.

Though other leadership options have been canvassed, Stone’s overwhelming preference is a restoration of Abbott:

Readers will know I have continued to believe the Coalition’s best chance at the next election will be by restoring Abbott as its Leader. A different choice, hailing from the party’s right (Peter Dutton?), would be enough to see many Dis-Cons stream back into the Liberal’s corner; but if the choice were Abbott, that stream would become a flood. Like him or loathe him, Abbott towers head and shoulders over anyone else in the Liberal party room, whether seen from a domestic policy viewpoint or as international statesman.

Minor party alternatives

However, while Turnbull remained in the job, disaffected conservatives were forced to consider placing their votes with other parties of the right. In the 2016 election, Stone recommended merely placing candidates from “acceptably ‘conservative’ parties” (such as Family First, the Australian Liberty Alliance, Fred Nile’s Christian Democrats and the Shooters and Fishers Party) above those Liberals who voted for Turnbull in the leadership spill.

But by April 2017, increasingly exasperated with the Liberal Party’s unwillingness to remove Turnbull, Stone was ready to abandon the party altogether:

If … nothing has been done by mid-year, we still loosely unattached Dis-Cons will need finally to make the break – to sever our former Liberal loyalties and definitively look elsewhere to lodge our votes. Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party, of course, beckons, as do the Liberal Democrats. Perhaps most attractive may be Cory Bernardi’s Conservative Party; but one way or the other, decision time approaches.

However, the recent electoral results of these alternatives have been decidedly underwhelming. One Nation seemingly came from nowhere to win four Senate seats in 2016, but performed significantly below expectations in subsequent state elections in Western Australia and Queensland.

The performance of Bernardi’s Australian Conservatives in the South Australian election in March this year was even more disappointing. Launched in April 2017 as the party for conservatives fed up with the direction of the Liberal Party under Turnbull, the party received a miserable 3% of votes in Bernardi’s home state, and has since suffered the defection of one MP to the Liberals.

Abbott’s relentless campaign

And so, an Abbott-led Liberal Party remains the goal for disaffected conservatives, and Abbott has proven more than willing to present himself as their flag-bearer. One report suggested he is preparing the ground for a return to the leadership in opposition, though Abbott publicly refuted the story.

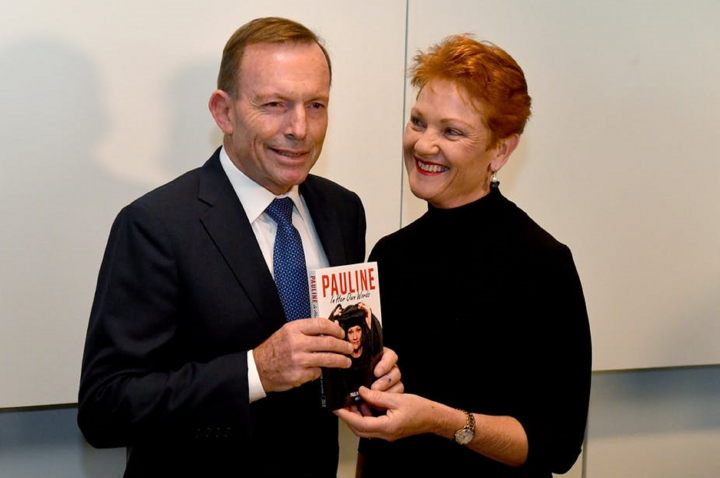

But the former prime minister continues his relentless campaign to undermine Turnbull’s leadership. He launched Pauline Hanson’s book at Parliament House, urging the Coalition to work with the “constructive” One Nation, and mischievously suggesting that “you are always better the second time around”.

Abbott is also a central figure in the Monash Forum, a loose collection of conservative Liberals and Nationals urging the government to invest in coal-fired power stations. Tellingly, the story of the group’s emergence was first broken by Peta Credlin, Abbott’s former chief of staff.

As they did in 2009, conservative MPs are exploiting internal divisions over climate and energy policy to undermine Turnbull’s leadership. The Monash Forum was slammed as “socialist” by Paul Kelly, and derided by Miranda Devine as merely “the usual suspects among the tiny delcon contingent of Liberal MPs”.

But though their numbers may be small, the delcons’ political impact is immense. They are determined to bring down the prime minister at any cost, including doing long-term damage to the Liberal Party.

This article is the second in a five-part series on the battle for conservative hearts and minds in Australian politics.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.