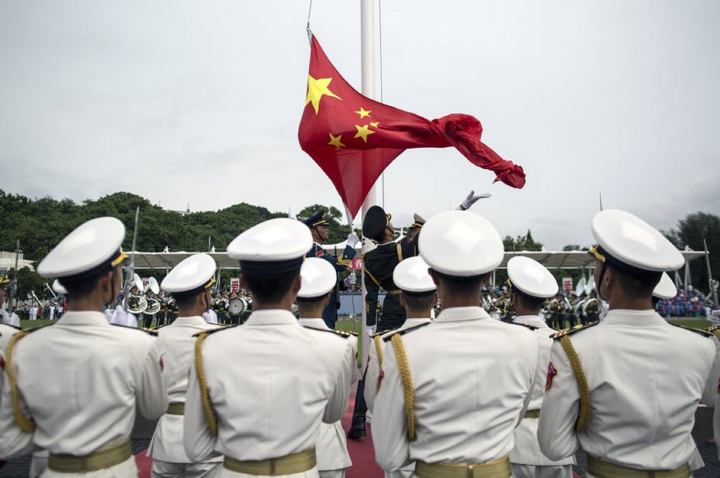

Rumour has it that Vanuatu has agreed to a Chinese request to establish a military base. The substance of this rumour is highly speculative at the least and disingenuous at most. Regardless of the truth, the fact that it raises alarm about the threat of Chinese military expansionism speaks volumes about Australian foreign policy, particularly toward the Pacific.

On Monday, Fairfax Media reported that “China had approached Vanuatu” about setting up a “permanent military presence” – in other words, a base.

The article went on to speculate about the dramatic strategic importance of the “globally significant move that could see the rising superpower sail warships on Australia’s doorstep”. Furthermore, this Chinese base “would … upend the long standing strategic balance in the region” and would likely be followed by bases elsewhere.

Multiple international media outlets have syndicated the story. Much of the coverage alluded to military threats and a shift in the strategic balance. The language is reminiscent of Cold War bipolarity: “their” gain is “our” loss.

On face value, this sounds like a serious geostrategic issue for Australia. But on close examination, the threat is more apparent than real. An indication of which is that nowhere are Chinese or Vanuatuan interests in provoking this form of strategic competition explained.

From the beginning, every assertion was countered by one of the primary players. Multiple representatives of the Vanuatu government have been at pains to deny the story. For instance, Vanuatu Foreign Minister Ralph Regenvanu was quoted as saying:

No-one in the Vanuatu Government has ever talked about a Chinese military base in Vanuatu of any sort.

Multiple Chinese government sources have denied the story and also described it as “fake news”. China also has assured the Australian government that the story has no validity.

In the original article, it was noted that talks between China and Vanuatu were only “preliminary discussions” and that “no formal proposals had been put to Vanuatu’s government.” So given these caveats, and the comprehensive denials, this raises some serious questions about why this rumour was newsworthy in the first place.

So where did it come from? Presumably Fairfax Media would only have acted if the information was from a highly placed Australian government source that could be verified. Presumably this unnamed source has leaked sensitive intelligence, but it is curious that no Australian Federal Police investigation has been announced.

This has been the past practice from the Turnbull government in relation to national security leaks, and there is no sign the government is at all concerned about this leak.

In contrast, it has used this rumour for megaphone diplomacy against both Vanuatu and China. For example, after accepting the Chinese government’s denial, the prime minister said:

We would view with great concern the establishment of any foreign military bases in those Pacific island countries and neighbours of ours.

And it was the latter rather than the former statement that was covered by many media outlets.

This is very telling. Canberra is clearly sending signals to Beijing and Port Vila that it maintains significant strategic interests in the region (and is a message not lost on other Pacific capitals).

This concern is not new as Australia practised strategic denial in the South Pacific against the Soviet Union during the Cold War. More recently, speculation about Fiji’s relations with China and Russia was raised. But megaphone diplomacy with Fiji has proven unsuccessful in the past.

This approach simply rehashes colonial tropes about Pacific Island Nations being economically unsustainable, corrupt, and easily influenced by great powers. This is reinforced by China’s alleged influence borne from budget support, and capital and aid flows into the Pacific.

What these colonial stereotypes fail to acknowledge is that the foreign policies of Pacific Island countries have matured. Vanuatu is a committed member of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), eschewing formal military alliances and entanglements with great powers. The lesson of Fiji’s strong stance against Australian sanctions is that it too has created an independent foreign policy. Neither country will be easily influenced by foreign powers, including Australia.

Returning to the “truth”. It is true that China’s influence in the region has grown dramatically in recent years, especially during the sanctions years from 2006 to 2014, when Canberra attempted to isolate Fiji.

It is also true that military diplomacy is a key element of China’s foreign policy approach (to the Pacific as in Africa). A final truth is that Vanuatu has a high level of debt dependence on China and is a major beneficiary of Chinese aid. However, this does not mean that Vanuatu is being influenced into accepting a Chinese military base.

At some stage, Vanuatu might very well sign an agreement that allows transit and refuelling of Chinese vessels, as is commonplace in international relations. As Minister for Foreign Affairs Julie Bishop told Radio National: “these sorts of visits are normal for many neighbours around the world.”

If so, then all we have learned from this episode is that old colonial habits die hard, and the chances of dispassionately dealing with the geo-strategic rise of China are narrowing.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation.