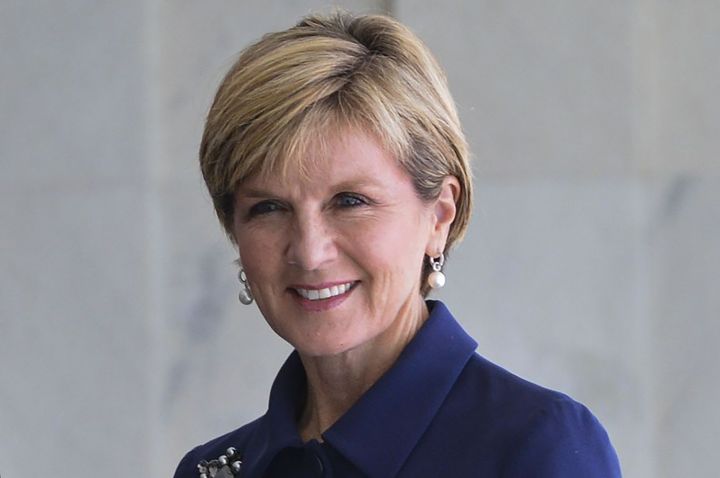

On 28 August, Julie Bishop resigned as Australia’s 38th foreign minister three weeks shy of marking five years in the job. Her tenure was the eighth longest since federation, an achievement all the more notable given the political turmoil of the past decade. As the first Australian woman to hold the office, and her stature in national politics, Bishop’s departure has led to more than the usual reflections on the mark she made on Australia’s place in the world during her time in the ministerial suite.

Operational excellence

Bishop was very highly regarded by the department and her staff. Her work ethic, ability to command the brief and capacity to develop effective personal relationships with her interlocutors abroad were widely known and greatly admired. Here, the contrast with her immediate predecessor could hardly have been more stark.

Bishop will also be regarded as a highly-effective departmental manager. This refers both to her ability to oversee the integration of AusAID into DFAT as well as the increase in the country’s international representation that she engineered. Bishop’s ability to reverse a long-term decline in the nation’s diplomatic footprint is a key achievement and one on which her successor, Marise Payne, must build.

While Bishop was institutionally very effective and had two outstanding secretaries of the department in Peter Varghese FAIIA and Frances Adamson, she was unable to reclaim DFAT’s role as a key strategic leader of Australian international policy, with the department continuing to be more on the tactical and operational side of the policy ledger.

Key achievements

The most immediate achievement was the creation of the ‘New Colombo Plan’ (NCP) launched soon after coming to power in 2013. Modelled on Liberal hero Percy Spender’s Colombo Plan, which brought university students from the region to Australia, Bishop’s new version sends Australians to Asia. The aim was to make studying in the region a rite of passage for young Australians. Signalling that Asia is not just a place for exotic backpacking, but somewhere to which one goes to learn, was hugely important.

Thousands of Australians have already enjoyed NCP study experiences, and it looks increasingly likely that a Labor government is likely to continue the program. The plan’s only major problem is one of scale. The vast bulk of students on NCP programs go on two-to-three week study tours and don’t really get the kind of long-term immersive experience that is necessary to foster the people-to-people links that the old plan achieved. Only around 100 per year go for more than a few weeks.

A Bishop Doctrine?

At the conceptual level, Bishop will be seen as a consolidator of two big ideas that had been part of the broader discussion of Australian international policy but which had, prior to her time in office, not yet become the lodestars of the country’s foreign engagement.

The Indo-Pacific is now firmly placed at the centre of the government’s rhetorical framing of its place in the world. While it emerged tentatively under the ALP Government that came before, it wasn’t until the 2016 Defence White Paper and the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper that the construct became firmly entrenched. Importantly, it is now also a key concept in the declaratory policy of the United States, India and Japan. But what is less clear is whether the government has the capacity and will to operationalise an Indo-Pacific policy; the substance to date of the Coalition Government (and indeed others who speak loftily in these terms) remains firmly focused on the Western Pacific side of that vast dual-ocean concept.

The other notion that Bishop concreted into Australian foreign policy is a strong and explicit commitment to the ‘rules-based international order.’ Like the Indo-Pacific, this concept had been part of the broader debate about Australia and the Asian region. But the adoption of the concept as a core aim of Australian foreign policy as a means to organise Australia’s response to the rise of China is in no small part due to Julie Bishop. At times, Bishop took this idea even further, being the most prominent voice nationally and in the region to advocate for an explicitly liberal set of values at the heart of that order.

But here is where the less effective side of her time in office become more visible. After the United States, Australia’s most important bilateral relationship is with the People’s Republic of China. And here, Bishop has to be marked down. She was not able to visit the country for the final two years of her term of office and the series of speeches she gave attempting to signal pushback only alienated the PRC and in no way led to any circumspection on Beijing’s part. This reflects a mismatch between the aims of short-term policy signalling with longer-term strategy. The difficult state of Australia-China relations is not entirely Bishop’s fault. But in both the way she contributed to the growing friction through deliberately-pitched speeches and the inability to frame a larger and more effective strategy toward the country’s most important trading partner, she is culpable in failing to help the country better navigate a contested Asia.

Julie Bishop was amongst the most effective holders of the foreign minister’s office with plenty of achievements to which she can point. Yet, there was no overarching big picture Bishop was painting on the regional or global canvass. This may reflect the institutional limitations of the foreign minister at a time of extremely strong prime ministers’ offices. But at a time of tectonic change in the region and the world, this shortcoming is all the more glaring. As time goes by, we will notice the opportunity Bishop missed to make a decisive impact in charting Australia’s course during a period of historical importance.

Originally published on the Australian Institute of International Affairs.