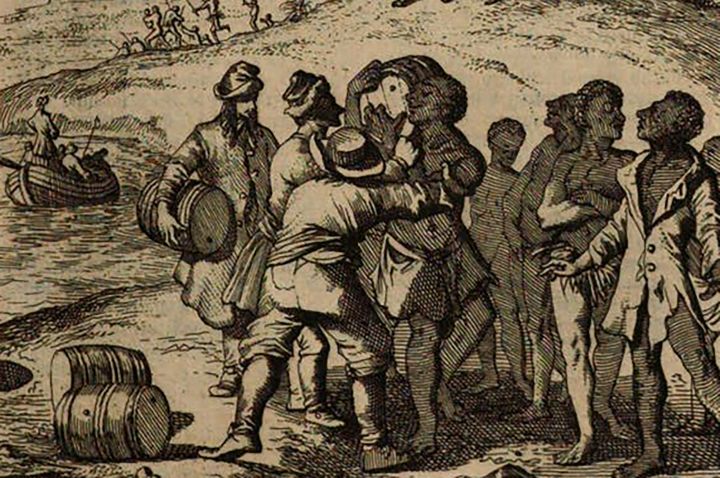

Seen today it unwittingly shows their resistance to the very first incursion by the English on Aboriginal land.

I found the image recently while I was researching in the rare books Pacific collection of the Hamilton library at Honolulu University. Until now the earliest printed image has been considered to be that by Sydney Parkinson, published by his brother (after a dispute with Banks) in 1773. Parkinson’s image, importantly, is still the first image from direct observation. It shows two Gweagal warriors challenging Cook’s landing at Botany Bay.

The new image, from 75 years earlier, was drawn from textual description, and comes from a little known edition of the explorer William Dampier’s journal, published in the Netherlands.

Dampier’s journal

William Dampier’s journal of his first circumnavigation of the globe was published in London in 1697 as A New Voyage Round the World and became a sensation, running to five English editions by 1706 and numerous translations. His exploits – roving, mutinying, sacking, scuttling and pillaging for 12 years throughout the Caribbean and beyond – captivated an increasingly literate public at the dawn of the Enlightenment, ravenous for descriptions of exotic species and “savage” peoples.

The image comes from an illustrated edition published in 1698 in the Netherlands. It took passages from Dampier’s unvarnished description and engraved them into copperplates.

These included a ship being tossed in high seas, a marooned “Moskito” Indian being rescued some years later, a live burial, a beheading, and “New Hollanders” refusing to carry barrels (p. 340) aboard the ship Dampier crewed, the Cygnet.

This remarkable visual vignette – now the earliest known printed European image of Indigenous Australians – was incised by an Amsterdam engraver and draughtsman Caspar Luyken for the printer Abraham De Hondt. The public was agog for accounts of the New World and particularly any reports of Terra Australis Incognita, the Great Southern Land first hypothesised by the Roman scholar Ptolemy in the second century.

Dampier had been searching for any sign of the Tryall, an English vessel which had been shipwrecked in 1622. He was one of 42 European landings and sightings along the Australian coast prior to James Cook (not to mention the Macassans, Sulawesi trepangers who traded with Aborigines along the northern coast as early as 1700).

Dampier had returned to London bereft of the spices and treasures by which other privateers enriched themselves. But he had with him a slave named Jeoly from the island of Miangas (an outlying island of now Indonesia) dubbed the Painted Prince Giolo, whom he displayed at the Blue Boar’s Head in Fleet Street, London. Jeoly and his mother had been bought by Dampier in Bencoolen, or British Bengkulu, in Sumatra. They had been brought in by one Mr Moody, a trader in “clove-bark”.

Dampier was clearly sanguine about slavery. He had previously worked on a plantation in Jamaica with more than 100 slaves and later lamented a lost opportunity of acquiring “some 1,000 Negroes” – “all lusty young men and women” – to enslave in a mine at Santa Maria.

‘New servants’

When Dampier imposed himself on the land of the Bardi-Jawi in King George Sound WA in January 1688 he experimented with the Indigenous people’s capacity to labour. This first known image of Australian Aboriginals is accompanied by a highly derogatory description.

It tells how the men were clothed (“to one an old pair of breeches, to another a ragged shirt, to the third a jacket that was scarce worth owning”) and made to carry barrels of water – “about six gallons in each”. The “new servants” were brought to the wells, and a barrel was put on each of their shoulders for them to carry to a canoe:

But all the signs we could make were to no purpose for they stood like statues without motion but grinned like so many monkeys staring one upon another: for these poor creatures seem not accustomed to carry burdens; and I believe that one of our ship-boys of 10 years old would carry as much as one of them. So we were forced to carry our water ourselves.

The men then took off the clothes and laid them down, “as if clothes were only to work in. I did not perceive that they had any great liking to them at first, neither did they seem to admire anything that we had”.

Poor creatures indeed – a life unencumbered by burdens. We can surmise they were more likely unaccustomed to assigning labour to others that they were perfectly capable of carrying out themselves, and in exchange for items of no value to them.

Aboriginal people did not enslave nor exploit. Dampier did capture “several” of the people here, giving them “victuals” before letting them go. And he wondered they would not “stir for us”.

With this description Dampier created a stereotype of Aboriginality that persists to this day, that of indolence. I’ve traced the entrenching of this trope through reprints of Dampier’s description into the 1950s, but I never imagined I would find it as the first printed European image of “New Hollanders”.

The image and Dampier’s journal attempts to enshrine Aboriginal people as “unfit for labour”, as this passage is bannered in later editions of Dampier’s journal. Instead the very first image of Aboriginal Australians is testament to their resistance by refusal, from very first contact with English to take up their burdens.

NB: This research will be presented at the Graphic Encounters Conference Wednesday to Friday this week, all welcome.

PHOTO: “New Hollanders” depicted in a 1698 edition of the explorer William Dampier’s journal. Courtesy of the Pacific Collection, Hamilton Library, University of Hawai'i-Mānoa

Originally published on The Conversation.